British American Tobacco

This page was last edited on at

Background

British American Tobacco (BAT) was established in 1902 when the Imperial Tobacco Company and the American Tobacco Company formed a new joint venture.12 Headquartered in London in the United Kingdom (UK), its businesses operate in all regions of the world.3 It operates as Reynolds American Inc. (RAI) in the US, after acquiring the company in 2017, and retains the name Imperial Tobacco in Canada (note that the UK based company Imperial Tobacco is now known as Imperial Brands). BAT is the second largest international tobacco company in the world (based on number of cigarettes sold), after Philip Morris International (PMI).4 This is excluding the Chinese National Tobacco Corporation (CNTC), with which BAT has a joint venture.156

According to Euromonitor International, in 2020, BAT held just over 12.2% of the total global cigarette market (by retail volume, including China, figures rounded).67 In June 2020, it reported total revenue of nearly UK£12.3 billion (US$16.5 billion), with 90% of its earnings coming from cigarettes and other conventional products.7

Popular BAT cigarette brands include Dunhill, Kent, Lucky Strike, Pall Mall, Rothmans and Camel.8 BAT also has a range of newer tobacco and nicotine products, including e-cigarettes (also known as electronic nicotine delivery systems, or ENDS) and heated tobacco products (see below for details). However, as BAT states “combustible cigarettes remain the largest global tobacco category”.9

Acquisitions and Interests

BAT owned 42.2% of RAI shares from 2004 to 2017.1 In January 2017, BAT announced that it had agreed to acquire the remaining 57.8% stake.10 This acquisition was completed by July 2017.111

In 2019, BAT held international interests with two other tobacco companies:1213

- ITC Private Limited (formerly known as the Indian Tobacco Company Private Limited): In 1985, BAT and ITC set up a joint venture in Nepal, the Surya Nepal Private Limited (Surya Nepal).1415 BAT owns 29.7% of ITC shares.1617 According to media reports, BAT unsuccessfully attempted to increase its stake in ITC on several occasions.181920

- China National Tobacco Corporation (CNTC): in August 2013, BAT and CNTC established a joint venture named CTBAT, which is headquartered in Hong Kong.5

In 1961, BAT diversified into paper, cosmetics and food industries. It also entered the retail industry, acquiring Argos and Saks Fifth Avenue in the UK and US, respectively. In the late 1980s, BAT moved into the insurance industry, acquiring Eagle Star, Allied Dunbar and Farmer’s Group in the UK. However, in the late 1990s BAT industries divested its non-tobacco business.1 Further historical background information can be found here.2

In the 2000s, the company once again diversified, this time into non-cigarette tobacco and nicotine products. BAT founded and wholly owns the Nicoventures group of companies. Nicoventures Ltd was set up as a division of BAT in 2011, originally dedicated to the production of licensed nicotine products.2122 A new holding company was set up in 2012, and from 2014 two subsidiaries focussed on different types of product:

- Nicoventures Trading Ltd – until 2014 named CN Creative, a company acquired by BAT in 2012. By 2014, this company was focussed on unlicensed products, including e-cigarettes.23

- Nicovations Ltd – in 2014, Nicoventures Ltd changed its name to Nicovations Ltd.24 This company’s focus remained licenced (or “regulatory approved”) inhaled nicotine products, including, for example, products licenced by the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).21 BAT had plans to develop a nicotine inhaler named Voke in a collaboration with the company Kind Consumer Limited, a project which was abandoned in January 2017.2526 By early 2018, the Nicovations website was no longer available, the company listed no employees and its only business activity was the leasing of equipment 27

Two further related subsidiaries were registered in the UK: Nicoventures U.S. Ltd (2015) and Nicoventures Retail (UK) Ltd (2016/17).

- BAT also owns Fiedler & Lundgren, a Swedish company which produces snus. See below for more on BAT’s non-cigarette products

In 2020, as part of its “transformation” agenda, BAT set up a new investment arm called Btomorrow Ventures.28 See below for details.

In January 2022, BAT announced the creation of biotech investment company KBio Holdings Limited (KBio) to “leverage the existing and extensive plant-based technology capabilities of BAT and Kentucky BioProcessing Inc”.29. For more information see Tobacco Companies Investments in Pharmaceutical Products and NRT.

Employees and Board Members: Past and Present

In May 2023, BAT announced that Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Jack Bowles was stepping down with immediate effect.30 Bowles had been appointed CEO in April 2019, succeeding Nicandro Durante.31

Bowles was replaced by Tadeu Marroco, previously BAT Group Finance Director.30

In October 2020, BAT announced that Richard Burrows would be stepping down as Chairman after the 2021 AGM.32 He would be replaced by Luc Jobin, who has a long history in the tobacco industry.33 Jobin held senior roles at Imperial Tobacco Canada from 1998 to 2005 and was Non-Executive Director of RAI before it was acquired by BAT, after which he became Non-Executive Director of BAT.33

A current list of BAT’s Board of Directors can be found on the BAT website.

Other persons that currently work for, or have previously been employed with, the company:

Jeffries Briginshaw | Jeannie Cameron (see JCIC International) | Kenneth Clarke | Mark Cobben | David Crow | David Fell | Ann Godbehere | Giovanni Giordano | Andrew Gray | Tomas Hammargren | Robert Lerwill | Jean-Marc Lévy | Adrian Marshall | Des Naughton | Christine Morin-Postel | Gerard Murphy | Shabanji Opukah | David O’Reilly | Kieran Poynter | Michael Prideaux | Anthony Ruys | Nicholas Scheele | Karen de Segundo | Naresh Sethi | Ben Stevens | Kingsley Wheaton | Neil Withington

Affiliations

Memberships and Partnerships

In 2019, BAT disclosed it was a member of the following associations:34

The American Chamber of Commerce to the European Union | British Chamber of Commerce in Belgium | BusinessEurope | Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) | Confederation of British Industry | Confederation of European Community Cigarette Manufacturers (CECCM; now Tobacco Europe) | European Cigar Manufacturers Association (ECMA) | European Smoking Tobacco Association (ESTA) | Institute of Economic Affairs | International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) UK | International Trademark Association (INTA) | ICC Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy (BASCAP) | Kangaroo Group|

According to BAT’s previous entries on the EU register it has also been a member of: 35 American European Community Association | European Policy Centre | European Risk Forum | Ad Hoc Council (The European Government Business Relations Council) | European Smokeless Tobacco Council (ESTOC) | The Mentor Group |

BAT is a member of the following trade and business associations: Association of Convenience Stores (UK) | UK Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association (TMA) | UK Vaping Industry Association (UKVIA) | Tobaksproducenterne (Tobacco Manufacturers Denmark)36 | Scottish Grocers’ Federation |

It has previously been a member of the following:

Czech Association for Branded Products | European Travel Retail Confederation | Federation of Wholesale Distributors | MARQUES | Scottish Wholesale Association | Tobacco Industry Platform (TIP) | Transatlantic Business Dialogue | UniteUnite |

BAT is also a founding member of the industry-funded Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing Foundation (ECLT).37 From 2002 to 2018, ECLT had a partnership with the International Labour Organization (ILO), a United Nations (UN) agency, focussed on issues related to labour such as international labour standards, social protection and unemployment.38

See below for more on BAT’s CSR activity relating to child labour.

BAT has also provided financial support to:

Alliance of Australian Retailers | Anti-Counterfeiting Group | All-Party Parliamentary Corporate Responsibility Group (APCRG) | All-Party Parliamentary Corporate Governance Group (APPCGG) | Business in the Community (UK) | Benkert | Business Action for Africa39 | Commonwealth Business Council | Conference Board40 | Consumer Choice Center | European Council on Research, Development and Innovation41 | European Science and Environment Forum | Forest | Forum for EU/US Legal-Economic Affairs | Global Reporting Initiative | Institute of Business Ethics | International Tax and Investment Center | International Tobacco Growers Association | The Common Sense Alliance | Rural Shops Alliance | VNO-NCW

Consultancies

In 2019, the following businesses listed BAT as a client:

Business Platform Europe42 | EUK Consulting | EUTOP Brussels SPRL43 | Red Flag

Other companies that have provided services for BAT include: Bernstein Public Policy44 | BXL Consulting | Bureau Veritas45 | Clifford Chance | Corporate Responsibility Consulting (CRC) | Crosby Textor Group | Edelman | FTI Consulting | Goddard Global | Hume Brophy | Instinctif Partners | Kantar | Morris and Chapman45 | Pappas & Associates 46 | Simply Europe47 | Weber Shandwick (see also Priti Patel)

Individuals that have consulted for BAT include: Axel Gietz | Delon Human | Peter Lee | John Luik | Carl V Phillips | Riccardo Polosa | Francis Roe

Think Tanks

The following think tanks have a history of being funded by BAT:

Centre for European Reform | Centre for Policy Studies | Chatham House | European Policy Centre | European Science and Environment Forum | Fraser Institute Free Market Foundation | Institute for Competitiveness (I-Com)| Institute of Economic Affairs | Institute of Public Affairs | Niagara Institute (See John Luik)

Controversial Marketing Strategies

Targeting Youth

Although BAT has stated that it is “committed to carry out youth smoking prevention”, the company has been accused of targeting youth in their marketing activities.4849

Some of the countries where the company has been accused of such tactics, include: Argentina50, Brazil,48 Ethiopia,51 Malawi,52 Mauritius,52 Nigeria,52 Sri Lanka, and Uganda.

Targeting Women and Girls

Women, who smoke less than men globally, are a key demographic for tobacco companies.53 Tobacco companies have identified packaging and brand design as important ways to appeal to women.

Large transnational tobacco companies have launched female-targeted brands. For example, in April 2011, BAT introduced Vogue Perle, described as “the UK’s first demi-slim cigarette”.54 BAT defended itself against claims it “downplayed” the health risks associated with smoking in favour of the “trappings of style, supermodels and staying slim”.55

Read more on our page Targeting Women and Girls.

Funding Education programmes

In 2011, BAT’s introduction of cigarettes targeted at women coincided with the revelation that the company was funding scholarships for four Afghan girls at Durham University. The university was criticised for accepting a GB£125,000 donation from BAT.56

The tobacco industry also attempts to enhance its reputation, and gain legitimacy, by funding universities. In 2000, Nottingham University came under scrutiny for its decision to accepts GB£3.8 million from BAT to establish an International Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility.575859

BAT has also funded education organisations and programmes as part of its CSR relating to child labour. For example, in 2001 BAT launched the “Our Florece” programme (meaning blossom) in Mexico, to set up and equip centres near tobacco growing farms providing migrant labourers’ children with access to education and health services.60

Read more on our page CSR: Education, and below for BAT’s other CSR activity.

Tactics to Subvert Tobacco Control Campaigns and Policies

Using British Diplomats to Lobby Foreign Governments on its Behalf

There have been several instances of senior UK diplomats lobbying governments on behalf of BAT in low and middle income countries (LMICs), including Bangladesh, Panama and Venezuela.

For more information, go to UK Diplomats Lobbying on Behalf of BAT.

Intimidating Governments with Litigation or Threat of Litigation

BAT has legally challenged the following tobacco control measures in the respective countries:

- Health Warnings/Plain Packaging in Australia (also see Plain Packaging in Australia and Australia: Trademark Claims), Namibia, Kenya, Sri Lanka, UK, and Scotland.61

- The Display Ban in the UK.

- The Tobacco Products Directive in the European Union (also see Legal Challenges).

- The Uganda Tobacco Control Bill 2014.

- The Kenya Tobacco Control Bill 2017, and 2014 regulations.

Fabricating Support through Front Groups

In May 2012, the Tobacco Control Research Group asked BAT to reveal the British-based think tanks it had funded during the previous five years, as well as those it had funded that were active in the plain packaging debate.

The company replied:

“British American Tobacco is happy to support those who believe in the same things we do – whether that be retailers against display bans or farmers against being forced out of growing tobacco;

* Our support may be financial support, or resources in kind;

* We do not tell these bodies what to say or how to spend the money;

* Many of the bodies, in particular the retailers, feel deeply patronised at the suggestion they are merely industry stooges.”62

In May 2013, in response to questions asked at the company’s Annual General Meeting by health advocacy Action on Smoking and Health, the company disclosed that it funded:63 FOREST, The Common Sense Alliance, Rural Shops Alliance, Scottish Wholesalers Alliance, Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association, and Tobacco Retailers’ Alliance

Also see: BAT Funded Lobbying Against Plain Packaging, The Plain Pack Group, Australia: Campaigning Websites, Australia: International Lobbying, Digital Coding & Tracking Association (DCTA)

- A list of tobacco industry allies can be found on the STOP website.

For more examples of BAT working through third parties, see the section below on its efforts to undermine illicit trade policy.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives

After its rebrand in 2020, BAT’s website prominently featured its “socially responsible” practices: “Our companies and our people ensure they are managed as responsibly as possible – from the crop in the fields through to the consumer”.64 TCRG research has revealed how the underlying motivation of BAT’s CSR and stakeholder management activities is to promote their corporate image, neutralise opposition and influence policy.65 Others have documented similar evidence, including in Malaysia66 and Malawi.67

CSR in Bangladesh

BAT Bangladesh (BATB) has close connections to government in the country due to its strategic CSR donations. BATB runs several programmes targeted at the environment, including reforestation, with the Bangladeshi Department for Agricultural Extension.68

Another BATB run programme, the Prerona Foundation, states that its goal is to “promote economic inclusion of marginalised communities, women empowerment and youth development through skills enhancement programmes”, and that its work is shaped by the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).69 Managing Director of BATB, Shezad Munim, stated that the Prerona Foundation was created to increase the scope of BATBs CSR activities.70 In 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the foundation introduced its own brand of hand sanitiser, reportedly distributing at least 100 000 units to different influential administrative bodies, law enforcement agencies and government institutions.7172

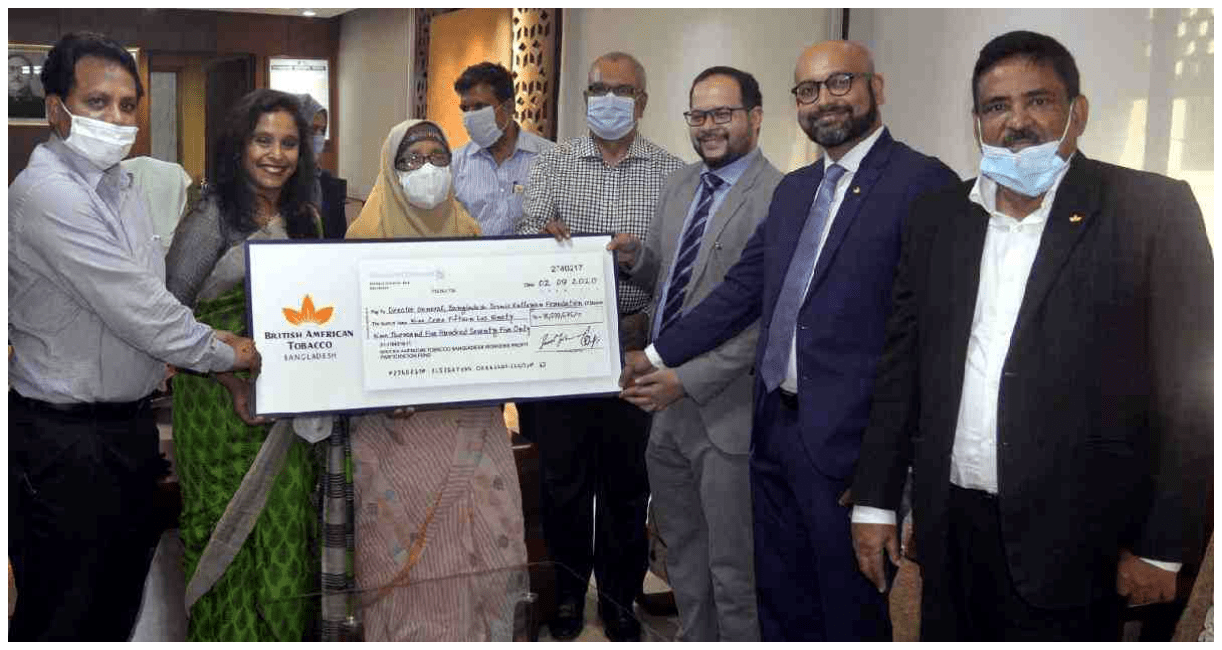

BATB has also provided direct donations to the government’s Welfare Fund, administered by the Ministry of Labour and Employment.73 These CSR programmes afford BATB access to influential government officials (Image 1). Between 2014 and 2017, BAT received five exemptions from the country’s labour law in clear violation of FCTC Article 5.3 Guideline 7.1, which prevents government from giving privileges or benefits to tobacco companies for simply running their business.74

Image 1: BAT Bangladesh employees handing over a cheque to State Minister for Labour and Employment Begum Mannujan Sufian in the conference room at the Secretariat in September 2020. (Source: United News of Bangladesh)

BAT’s assertions also do not line up with its business practices. Apart from evading labour laws in Bangladesh, the company faces a lawsuit over its alleged use of child labour75 and stands accused of using bribery to undermine tobacco control legislation and weaken competition in Africa.76

- More on way the industry, including BAT, uses environmental reporting and CSR programmes to greenwash its business practices can be found on Greenwashing. A general overview of industry CSR techniques is on the CSR Strategy page.

- You can read more about BAT’s rebrand and how it aligns with its newer products strategy on Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: British American Tobacco.

Influencing Science and Scientists

Documents in the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents collection, an archive of previously secret tobacco industry documents, reveal BAT’s efforts to mislead the public on the science of smoking and disease. In 1958, BAT scientists, alongside other industry scientists, understood that smoking caused lung cancer. BAT’s public denial of this fact continued into the 1980’s, when, according to an internal BAT memo, it changed direction, to acknowledge “the probability that smoking is harmful to a small percentage of heavy smokers”.77

Documents from the 1970s show BAT scientists had confirmed that second-hand smoke, also known as environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), was harmful. However, in public, BAT lawyers denied the harm, saying: “the question is not really one of a health hazard but perhaps more of an annoyance”.78 To distract from health concerns such as ETS, in the late 1980s BAT discussed the need for a public relations (PR) and political campaign focussed on protecting smokers’ rights.79 It also funded research into ‘sick buildings’, to promote the idea that building design was responsible for ill health rather than ETS. A review of the Truth Tobacco documents covering the period 1985 – 1995 concluded that “At times scientists seemed to be acting more like public relations specialists than scientists.”80

On the science of addiction, the Truth Tobacco documents show that scientists working for BAT, and its subsidiary Brown and Williamson, concluded in the early 1960s that nicotine was addictive. Despite this, in 1994, the CEO of Brown and Williamson, testified before the US Congress alongside the CEOs of Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds (later acquired by BAT). Each said: “I believe nicotine is not addictive.”81

To prevent the release of further scientific documents in the 1980s, lawyers advised BAT not to conduct research in countries where legal action might be taken against the company.82

In Europe in the 1990s, BAT worked to secure the right for the tobacco industry to be consulted on any tobacco policy informed by science, allowing tobacco companies to self-police, despite the clear conflict of interest.83

- For more information see the pages on: Influencing Science

Involvement in the illicit tobacco trade

Like other transnational tobacco companies, BAT has a long history of facilitating tobacco smuggling. For example, internal BAT documents from the 1980s and 1990s revealed that in Africa, BAT used the smuggling of its own products as a business strategy to achieve a range of objectives including: gaining access to emerging markets, gaining leverage in negotiating with governments, competing for market share and circumventing local import restrictions.84

In September 2000, BAT faced action by the Departments (States) of Colombia which alleged that it committed violations of racketeering laws: “…arising from its involvement in organized crime in pursuit of a massive, ongoing smuggling scheme”.8586

In 2008, BAT subsidiary Imperial Tobacco Canada pleaded guilty to customs charges related to cigarette smuggling.

In 2010, BAT signed a cooperation agreement with the European Union (European Control Association, EUCA) and its member states to help tackle illicit tobacco trade. BAT agreed to pay the EU US$200 million over 20 years. “In return, the manufacturers are released from any civil claims arising out of past conduct relating to illicit trade”, a UK government press release pointed out.87

In 2014, HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) fined BAT for oversupplying the Belgian market- a practice which can facilitate the smuggling of products across borders.88

In 2021, BAT stated it “had agreed to dispose of” its subsidiary in Iran.89 It did not provide further detail on the reasons for its departure from a country in which it held the second largest market share,90 and generated approximately UK£170 million in revenue and UK£60 million in profit in 2020.91 In April 2023, following a criminal investigation by US authorities, BAT agreed to pay penalties exceeding US$629 million to resolve charges of bank fraud and sanctions violations charges in North Korea, another country facing international sanctions.92 In a press release, BAT stated in response that “adhering to rigorous compliance and ethics standards has been, and remains, a top priority”.93 In 2023 TCRG published research on BAT’s activities in Iran.94 Using internal BAT documents covering 2000-2014, the paper – through the case study of Iran – tests the credibility of BAT’s claim to adhere to compliance and ethics standards. It points to BAT’s potential involvement in illicit tobacco trade, and explains how BAT’s extensive engagement with government authorities to tackle illicit trade focused primarily on reputational and commercial purposes, at the expense of controlling its own supply chain.94

- For more details see BAT Involvement in Tobacco Smuggling

Efforts to undermine policy to address illicit tobacco trade

Previous TCRG research has outlined how tobacco companies, including BAT, have attempted to interfere with the implementation of tracking and tracing implementation. This included using front groups (such as the Digital Coding and Tracking Association) to promote their own ineffective and inefficient technology, formerly knowns as Codentify (now the Inexto Suite). In Kenya in 2012, BAT unsuccessfully tried to influence a track and trace tender outcome in favour of the Codentify system through the use of a third party, Fracturecode.Internal industry documents indicate that Fracturecode was closely linked to BAT. For more details, see our page, Kenya- BAT’s Tactics to Influence Track and Trace Tender.

In 2016 the European Union (EU) ran a public consultation for the European Union’s track and track system. TCRG research (published in October 2020) found that the tobacco industry lobbied extensively for the EU to adopt a system controlled by the industry. Transnational tobacco company’s interests were repeatedly represented through consultation submissions by multiple trade associations, which were not always transparent about their membership. .95 For more details see Track and Trace.

Limiting Its Tax Bills

TCRG research published in March 2020 found that “Very little profit based taxation has been paid in the UK [by tobacco companies] despite high levels of reported profits, both in the domestic market and globally.”96 While BAT has a relatively small share of the UK tobacco market (less than 10%), the company made hundreds of millions estimated profit in the UK and hundreds of billions globally. However, since 2010 it has paid virtually no UK corporation tax (effectively 0%) despite paying 20-30% in other countries.96

An investigation by journalists from the Investigative Desk and TCRG researchers, found that BAT uses “aggressive tax planning” strategies to reduce the amount of tax it pays.9798

Analysis of BAT company reports between 2010 and 2019, found that BAT (and the other main transnational tobacco companies, PMI, JTI and Imperial) use several methods to avoid or lower their tax bills:97

- Shifting dividends – for example, each year BAT shifts around €1 billion in dividends via Belgium, paying tax at less than 1 percent.

- Group relief – losses from interest paid on internal loans lead to group tax relief, meaning BAT paid almost no UK corporation tax.

- Notional interest deduction – €3.5 billion in assets were held in holding companies in Belgium, helping BAT to deduct several millions in notional (fictitious) interest between 2010-2017.

- Profit shifting via intra-firm transactions – for example, BAT Korea Manufacturing Ltd in South Korea sold its cigarettes – on paper – to Rothmans Far East, another BAT subsidiary. The cigarettes were then re-sold back to BAT Korea Ltd at a much higher price. By this method BAT moved an average of €98m of Korean profits to the Netherlands.

BAT was able to reduce its tax bill by an estimated £760 million over 10 years.97 While seen as morally wrong by many, or at least socially undesirable, tax avoidance is not illegal; it is sometimes referred to as ‘tax planning’, whereas tax evasion is a crime. However BAT’s activities do not even appear to be in the spirit of its own code of business conduct.99. BAT states that it “complies with all applicable tax legislation and regulations in the countries where we operate”.100 However, as of November 2020, BAT had been, or was still, involved in tax disputes in multiple countries: Netherlands (the largest claim,€1.2 billion), Brazil, South Korea and Egypt.97 In September 2019, the European Commission announced an investigation into tax avoidance by 39 multinational companies, including BAT.97101

You can read more about the tobacco industry and taxation on our page, Price and Tax.

Behtr Pakistan Campaign

BAT has also developed PR campaigns to support its goals to reduce its tax bill. The Behtr Pakistan campaign was launched in 2021 and states that it aims to “to create awareness about tax collection in Pakistan, identify effective solutions to enhance tax collection and make the country progress”. The campaign represents itself as a “nationwide public service, national interest initiative” but was created by Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited, a subsidiary of British American Tobacco.102 Behtr Pakistan uses arguments regularly used by the industry, stating that increased taxes in the tobacco sector have resulted in an increase in illicit trade.103

Accusations of Corruption and Bribery in Africa

From 2017 to 2021, BAT was under investigation by the UK Serious Fraud Office (SFO) after allegations of corruption and bribery in Africa.76104105106In January 2021 the SFO announced it was closing the investigation saying: “The evidence in this case did not meet the evidential test for prosecution as defined in the Code for Crown Prosecutors.”107

Further accusations followed in 2021. Read The BAT Files, which detail how BAT bought influence, interfered with tobacco control measures, and undermined its competitors across the continent.

BAT has consistently denied the allegations.108

Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products

As the harms from conventional products have become better understood, and tobacco control measures have been put in place, the cigarette market – from which tobacco companies make most of their profits – has started to shrink. To secure the industry’s longer-term future, transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) have invested in, developed and marketed various newer nicotine and tobacco products.109 BAT also has an interest in new cannabis products (see below).

In March 2020, BAT rebranded its corporate website with the tagline “A Better Tomorrow”, which was originally registered by Nicoventures and used to promote BAT’s newer products. However, in 2020, over 90% of BAT’s revenue still came from cigarettes and other conventional tobacco products.7 It also stated that its revenue growth since 2019 “was driven by combustibles”.7

To read more about BAT’s products and strategy, including its 2020 rebrand, visit our page Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: British American Tobacco.

BAT Expansion “Beyond Nicotine”

BAT has been accused of “health washing” its reputation by connecting itself to wellness products while continuing to sell tobacco products: there are concerns that the ‘health halo’ from wellness products could normalise its brand. The health claims of many wellness products in general have been described as ‘baseless’ but make good sales due to effective marketing.110

Btomorrow Ventures

In 2020, BAT set up a new investment unit called Btomorrow Ventures.111 As part of a “transformation”, BAT announced plans to go “beyond nicotine”.112 The new division invited investment in areas ranging from “BioTech & Science, Technology, Wellbeing & Stimulation to Environmental Social Governance”.28113 BAT launched a dedicated website in July 2021 and invited companies to pitch for investment to help “accelerate this transformation”, specifically those relating to “digital transformation” and the “sustainability agenda” (see Greenwashing).28114

- BAT’s current investments can be found on the BTomorrow Ventures website

The Waterstreet Collective

In April 2022, The Waterstreet Collective, a company wholly owned by BAT, was registered at UK Companies House.115 for “the development, procurement, marketing and sale of wellbeing and stimulation products and associated accessories”.116. Its Ryde drinks are made in the US and have been marketed in Canada and Australia.117118 Free samples were handed out to Australian university students without BAT’s ownership being disclosed to the students or the university, or on the product packaging.110 As of January 2024, The Waterstreet Collective LinkedIn Profile states that it “partners” with Btomorrow Ventures.119

- For more information see pages on Tobacco Companies Investments in Pharmaceutical Products and NRT and Cannabis

TobaccoTactics Resources

- The BAT Files

- British American Tobacco in Africa: A History of Double Standards.

- UK Diplomats Lobbying on Behalf of BAT

- BAT Involvement in Tobacco Smuggling

- Imperial Tobacco Canada: Involvement in Cigarette Smuggling

- Kenya- BAT’s Tactics to Undermine the Tobacco Control Regulations

- Kenya- BAT’s Tactics to Influence Track and Trace Tender

- Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: British American Tobacco

Relevant Link

- British American Tobacco company website

- Btomorrow Ventures website

TCRG Research

- “Unlawful Bribes?”: A documentary analysis showing British American Tobacco’s use of payments to secure policy and competitive advantage in Africa, R.R. Jackson, A. Rowell, A.B. Gilmore, 13 September 2021, UCSF: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education. Available from: escholarship.org/uc/item/4qs8m106

- The Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility: Techniques of Neutralization, Stakeholder Management and Political CSR, G. Fooks, A. Gilmore, J. Collin et al, Journal of Business Ethics, 2013, 112:283. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1250-5

- “Working the System”—British American Tobacco’s Influence on the European Union Treaty and Its Implications for Policy: An Analysis of Internal Tobacco Industry Documents, K.E. Smith, G. Fooks, J. Collin, et al, PLoS Med, 2010; 7(1): e1000202, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000202

- Trade policy, health and corporate influence: British American Tobacco and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, C. Holden, K. Lee, A. Gilmore et al, International Journal of Health Services, 2010, 40: 421-441, doi:10.2190%2FHS.40.3.c

- The invisible hand: how British American Tobacco precluded competition in Uzbekistan, A.B. Gilmore, M. McKee, J. Collin, Tobacco Control, 2007; 16:239-247, doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017129

- “The law was actually drafted by us but the Government is to be congratulated on its wise actions”: British American Tobacco and public policy in Kenya, P. Patel, J. Collin, A.B. Gilmore Tobacco Control, 2007; 16:e1, doi:10.1136/tc.2006.016071

- British American Tobacco’s erosion of health legislation in Uzbekistan, A.B. Gilmore, J. Collin, M. McKee, BMJ, 2006; 332-355, doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7537.355

For a comprehensive list of all TCRG publications, including TCRG research that evaluates the impact of public health policy, go to TCRG publications.