Heated Tobacco Products

This page was last edited on at

As the harms from conventional products have become better understood, and tobacco control measures have been put in place, the cigarette market – from which tobacco companies make most of their profits – has started to shrink. To secure the industry’s longer-term future, transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) have invested in, developed and marketed various newer nicotine and tobacco products.1

Since the early 2000s TTCs have developed interests in e-cigarettes (also known as electronic delivery systems, or ENDS), heated tobacco products (HTPs), snus and nicotine pouches. Companies have referred to these types of product as ‘next generation products’ (NGPs) although terminology changes over time.

- See the product terminology page for more details, including terms favoured by the industry.

This page focuses on HTPs. It explains what these products are, summarises tobacco company investments in this product segment, and discusses the main public health debates around these products. It does not include all research updates on the potential health benefits/risks of HTPs but does refer to some key and emerging independent analyses. It primarily looks at how the tobacco industry uses its own scientific studies, and the concept of harm reduction, to further its business goals.

Background

Unlike e-cigarettes, HTPs contain tobacco.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) describes the tobacco in these products as being “heated without reaching ignition to produce an emission containing nicotine and other chemicals”.3 According to tobacco companies, by heating the tobacco, rather than burning like conventional cigarettes, the formation of harmful substances created at high temperature associated with combustion is significantly reduced.4 This tobacco industry reduced-risk claim has yet to be fully supported by independent scientific evidence, as discussed below. IQOS, produced by Philip Morris International (PMI) is the most widely available HTP, with by far the biggest share of the heated tobacco market, but the other big three transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) all now have HTPs, Imperial Brands being the last to launch a product in 2019 (see below). South Korean tobacco company KT&G also has a growing share of the HTP market and, in 2020, a new partnership with PMI to commercialise KT&G’s range of Lil HTPs and e-cigarettes.56 China National Tobacco also has an HTP called Mok.78 This page focuses on the four main transnational tobacco companies and their interests in HTPs.

In 2017, the British Government classified HTPs into three categories:9

- Processed tobacco heated directly to produce vapour;

- Processed tobacco designed to be heated in a vaporiser;

- Devices that produce vapour from non-tobacco sources, where the vapour is then passed over processed tobacco to flavour the vapour.[referred to here as HTP ‘hybrids’]

In its 2020 briefing the WHO identified the same three types, with the addition of new carbon tipped devices.3

The images below show examples of tobacco companies’ HTPs. The images are screenshots from the manufacturers’ websites taken in June 2017, with the exception of Imperial’s Pulze (2019).10

Image 1. PMI’s IQOS

Image 2. BAT’s iFuse

Image 3. JTI’s PloomTech

Image 4. BAT’s glo

Image 5: Imperial’s Pulze

Despite significant media attention on the tobacco industry’s HTP pursuits,111213 and the technology being initially marketed as “a real game changer”,14 HTPs still represent a small proportion of the global tobacco market and conventional tobacco products (mainly cigarettes) continue to dominate.

Heated Tobacco Product Technology Pioneered in 1980s

Image 7: Accord Advertisement by Starcom Media Services15

HTP technology is not new. It was first developed by tobacco companies in the 1980s to address concerns about second-hand smoke exposure. In 1988, the American tobacco company RJ Reynolds (RJR) launched the first HTP, Premier, in several American cities.1617 The company’s objective behind developing Premier was to “produce a cigarette which provided the enjoyment and satisfaction of other cigarettes, but without many of the perceived negatives”.16 Richard Kampe, then President RJR Development, said: “What it all comes down to is a cleaner smoke for smokers and those around them”.18 Premier was withdrawn from the market in early 1989 reportedly because smokers “did not like Premier’s taste or smell”.19

In 1996, RJR started test marketing its second HTP, called Eclipse, marketed to smokers under the slogan “imagine the unimaginable”.20 The company purported that Eclipse was a new cigarette “with nearly 90 percent less second-hand smoke”.21 This claim was refuted in 2002 by an independent study which found that Eclipse was at least as toxic as conventional cigarettes.22 The product was on the American market until 2014.23

In 1998, Philip Morris launched its first HTP, called Accord, under the slogan “the time is right” (Image 7).24 The company commissioned Starcom Media Service to run a media campaign to create awareness of the product and communicate its perceived benefits, including reduced second-hand smoke, smoke odour and ash.1525 Accord remained on the market until 2006, when it was discontinued due to poor sales.26 Consumers allegedly complained that the product was not as satisfying as conventional cigarettes.26 In 2007, PMI briefly rebranded Accord to Heatbar and trialled the product on the Swiss and Australian markets. It’s unclear when the product was withdrawn from these markets.27

It appears as though none of the early HTPs gained commercial success, and none were marketed as potentially less harmful. A 2016 study by Dutra et al.28 concluded that the tobacco industry’s early HTP pursuits were primarily driven by non-health related reasons: to evade smoke-free regulations and to complement, rather than compete with, conventional cigarettes.

A New Take on an Old Idea

2014 marked the start of a phase of new HTP launches by tobacco companies. RJR (by then owned by British American Tobacco) launched Revo (allegedly a revamped version of Eclipse) under the banner “an unconventional cigarette”,29 PMI introduced IQOS (allegedly a revamped version of Accord)30 under the banner “this changes everything”,31 and BAT launched iFuse in 2015.32

By early 2018, all transnational tobacco companies except Imperial Tobacco had included HTPs in their product portfolio. PMI promoted them as part of its purported goal of a “smoke-free future” and BAT framed them as part of its “Transforming Tobacco” programme.333435 In 2019, Imperial Tobacco (now Imperial Brands) also launched an HTP.36

By 2019, BAT and PMI were testing devices using a carbon tip as the heat source (details below).

Japan Tobacco International

In 2010, JTI acquired a 27% share in San Francisco-based entrepreneurial company Ploom Inc., signing an agreement to commercialise Ploom Inc.’s HTP outside the US.37 In February 2015, JTI and Ploom (later trading under the name ‘Pax Labs’) ended their partnership and JTI acquired the intellectual property rights for Ploom HTPs.38 One year later, JTI launched an upgraded version, called PloomTech.39 These HTPs heat small pods of tobacco, through a capsule of e-liquid, and so are referred to on TobaccoTactics as HTP ‘hybrids’. JTI’s hybrids are sold under the Ploom TECH and Ploom TECH+ (launched 2019) brands,40 with the accompanying capsules sold under the Mevius and Pianissimo brands.4142 In the US, Ploom TECH is marketed as Logic Vapeleaf.43

JTI added Ploom S and Ploom X to its portfolio, in 2019 and 2021 respectively.40 Unlike the hybrids, these use tobacco sticks, sold under the Mevius, Camel, and EVO brands.4445

- For more details see Newer Nicotine & Tobacco Products: Japan Tobacco International

Philip Morris International

PMI first launched IQOS 46 in the second half of 2014 in Italy, and later trialled the product in Japan.47 It was reported at the time that IQOS stood for I Quit Ordinary Smoking. However, this claim has been denied by PMI, and tobacco control researchers warn against the use of this misleading term.48

The electronic device heats tobacco sticks, originally called HEETS and later sold under various brand names and in different flavours.49 PMI’s 2021 annual report stated that “[a]s of year-end, our smoke-free products were available in 71 markets, of which 30 are classified as low- and middle-income markets.” (Note that this may have included some markets where only its e-cigarette Veev was available).50

PMI applied to have IQOS classified as a Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2016.5152 On 7th July 2020, PMI was granted an exposure modification order for IQOS, but denied a risk modification order. In line with the Tobacco Products Advisory Committee recommendation in 2018,53 the FDA concluded that the data PMI submitted showed that IQOS may reduce exposure to harmful substances, it did not agree that IQOS reduces the risk of disease and death, compared to smoking cigarettes, and so had failed to meet the higher standard of “risk modification”.545556

- For details of the FDA’s decision, the implications and PMI’s reaction, see Heated Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International and PMI Promotion of IQOS Using FDA MRTP Order.

Altria has an agreement with PMI to distribute and market its HTPs and e-cigarettes in the US. PMI also has a distribution deal with South Korean tobacco company KT&G for its ‘lil’ products.

PMI has been testing a carbon tip device, called TEEPS 5758 This is likely to be similar to BAT’s Neocore device (see below). Both companies have stated that these products resemble traditional cigarettes.575859 In its 2021 annual report, PMI stated it had discontinued the current TEEPS technology following feedback from consumer testing in late 2021.50

In September 2023, PMI announced that it had developed a product for IQOS devices called LEVIA containing “non-tobacco substrate infused with nicotine and tobacco, menthol and fruit flavourings.4960 It appeared that this was developed in order to circumvent regulations which apply to heat sticks containing tobacco, specifically bans on flavours.4960

- For details of both of the above see Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International

British American Tobacco

BAT initially focused its newer product investment on e-cigarettes (for more detail see the page on E-cigarettes: British American Tobacco). In 2015, BAT entered the HTP market with the launch of iFuse, a product that heats an e-liquid, which creates a vapour which is passed through a tobacco pod (similar to JTI’s PloomTech).61 In 2016, BAT launched glo, which the company claimed was “a real game changer for consumers”.14 Like IQOS, glo uses a battery operated device to heat tobacco sticks (called Neostiks and sold under BAT’s cigarette brand Kent).6263 According to BAT, glo is a simpler and more practical alternative to IQOS.64 In 2017, the product was sold in five countries.65 By 2019, glo was sold mainly in the large markets of Japan and South Korea, and the product was being rolled out in other countries, including in Eastern Europe, Russia and Canada,6667 although it was discontinued in Canada in 2019 in favour of BAT’s e-cigarette Vype.68 By January 2023, BAT stated that glo was available in 25 markets, with 20 listed on the glo website.6970

The company was also developing a carbon tip device, under the name NeoCore.59 This appeared to be a version of an earlier Reynolds product Revo, renamed Eclipse (BAT acquired Reynolds American Inc. and its subsidiaries in 2017).59 Although Neocore was cleared for sale by the FDA, and BAT were reported to be testing the product with consumers in 2018,71 it did not appear on the market and by July 2020 was no longer on BAT’s website.597072

In October 2023, similarly to PMI, BAT announced that it had launched a new non-tobacco stick for glo, called veo, made with Rooibos tea leaves, and infused with nicotine and flavours.737475

- For more information see Newer Nicotine & Tobacco Products: British American Tobacco

Imperial Brands

At the end of 2017, Imperial Brands (previously Imperial Tobacco) was the only transnational tobacco company not selling HTPs. The company’s newer product strategy had largely focused on e-cigarettes, and it had publicly dismissed HTP health claims made by its competitors, asserting “there’s no difference really between those products and traditional tobacco products” and “It’s probably better described generically as ‘heat and burn’ rather than ‘heat not burn’”.76 In 2015, Imperial Tobacco scientists published a study in the Environmental Analytical Chemistry journal that concluded that PMI’s IQOS released tobacco-containing side stream emissions, and as such, the scientists recommended that HTPs should be covered by smoke-free legislation.77

However in early 2018, apparently under pressure from shareholders, Imperial announced that it was after all developing and trialling HTPs.78798081 In May 2019, Imperial’s HTP Pulze was launched in Fukuako, Japan.828384 As of 2023, Imperial’s HTP appeared to be undergoing consumer testing in Greece and the Czech Republic.85

- For more details go to Newer Nicotine & Tobacco Products: Imperial Brands

Global HTP Market

Rapid growth

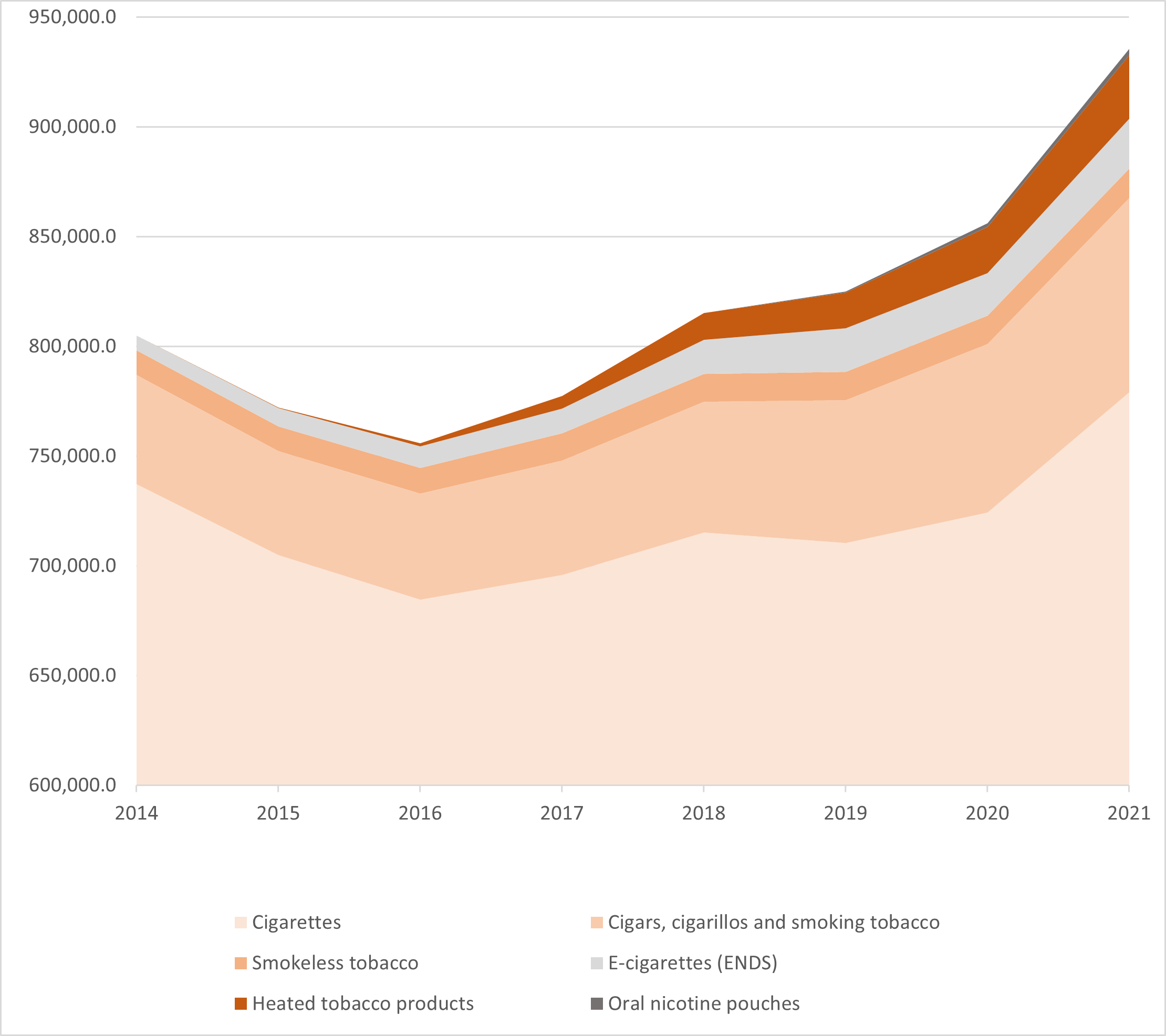

Since 2014, the HTP market has grown rapidly, but remains dominated by PMI (see Figure 1 below). According to Euromonitor International, in 2021 around 30 million devices and 125 billion sticks were sold, and the value of the global retail market was close to US$30 billion.86

Figure 1: Relative retail value of tobacco products, in $US, 2014-2021. NB graph shows values above US$600,000 million. (Source: Euromonitor International)

Devices vs sticks

The composition of retail sales changed over this period. In 2014, HTP sticks accounted for around one third of the total by value, and devices for the remaining two thirds. By 2021, the sticks made up over 90%.86 This is likely due to the high initial uptake and purchase of devices.

Company shares

In terms of company market shares, slightly different pictures emerge for devices and sticks. The devices, which do not contain any tobacco, are bought separately and less frequently than the sticks. Thus, the market share for HTP sticks should be considered comparable to the cigarette market. In 2016, PMI held three quarters of the device market and most of the HTP stick market.86 Over the next few years, JTI and BAT began to challenge this dominance, with Ploom and glo devices respectively. Since 2018, PMI’s share of the market for HTP devices has fluctuated between half and three quarters.86 KT&G’s share was increasing prior to its distribution deal with PMI in 2020.86 Although PMI’s share of the HTP stick market has also been challenged by BAT and JTI, in 2021it continues to dominate:86

Key markets

The key regional markets for HTPs are in South East Asia, which accounted for over half the total global value by 2020. Japan remains by far the biggest single country market for HTPs.

The WHO stated in 2020, that HTPs may still be available in markets where they are in theory banned from sale.87 See below for more on the regulation of HTPs.

Still a Small Part of the Global Tobacco Business

According to Euromonitor data, in 2021, HTPs represented 3% of the global retail value of all tobacco products.86 This represents a doubling in value since 2018, and now appears to have overtaken that of e-cigarettes. Smokeless tobacco accounts for a smaller share, around 1%. (Note that Euromonitor does not include nicotine pouches, which do not contain tobacco leaf, in its smokeless tobacco data).86

Cigarettes and other conventional tobacco products still represent the bulk of the market and are likely to do so for the foreseeable future.

HTP Adoption Rates

Japan and South Korea

BAT, PMI and JTI have used Japan, and to a lesser degree South Korea, as trial markets for their HTPs. Both tobacco markets are dominated by companies which were former state monopolies, Japan Tobacco and Korea Tomorrow & Global Corporation (KT&G), with PMI in second place in both cases. Both had very high smoking rates and a preference for low tar brands, which may make alternatives more appealing.88

Preliminary sales reports by the tobacco companies and industry analysts showed strong adoption rates of HTPs. According to PMI, by March 2017 the tobacco company had sold three million IQOS devices in Japan, saying that “demand continues to outstrip supply”.89 In 2018, BAT’s market research, conducted by Kantar estimated the prevalence of HTP use was much higher at around 5%.90 However, the sample was drawn from three urban areas, and therefore was not representative of the whole population. This study did not identify brand preferences.

Independent academic analysis of data from the 2018 International Tobacco Control (ITC) Japan Survey, a nationally representative web survey, found that the overall prevalence of HTP use was 2.7% , equivalent to nearly 4.4 million people if applied to the whole population of Japan.91 The researchers found that over 60% of HTP users reported using IQOS devices (representing approximately 2.6 million people).91 IQOS was preferred by younger people and daily users, while JTI’s Ploom TECH was more popular among older people and less regular users.91. In contrast to PMI’s claims, the researchers found that most users of HTPs also smoked combustible cigarettes.91

It has been suggested that the success of HTPs in Japan might be connected to restrictive e-cigarettes being banned in the region.9291 E-cigarettes containing nicotine liquid are covered by pharmaceutical regulation, and as of 2020 have not been approved for sale in Japan.93 Japanese consumers being more receptive to innovative products,65 and cultural values prevalent in Japan which do not necessarily apply to other markets.9495

Researchers have raised concerns that as IQOS was marketed in Japan as a high tech, aspirational product it might appeal more to youth and young adults.9195 A study based on 2017 data found that HTPs were being used by Japanese adolescents, although still at lower rates than combustibles and e-cigarettes.96

Philip Morris used a similar marketing approach when it launched IQOS in South Korea in June 2017.97 Research conducted three months later found that “Awareness, experience and use of IQOS among young Korean adults were relatively higher than among their Japanese counterparts”.98 Subsequent studies found high poly use of products (HTPs, e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes) among young people in South Korea.99100

A 2023 systematic review conducted by independent academics found the prevalence of HTP use had increased between 2015 and 2020 in four countries from the Western Pacific Region (Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan).101 According to the reviewed data, the region had higher prevalence of HTP use than the other regions. Indeed, reports from Japan and South Korea indicating prevalence of current HTP use was over 10% – two of only three countries included in the review for which double-digit current use prevalence has been reported (the third being Bulgaria).101

Europe and North America

A recent survey of over 40,000 US adults found that over 8% were aware of HTPs, but only 0.5% reported ever using them (all figures rounded). The data also showed adult use of HTPs was higher amongst current users of other nicotine and tobacco products, like cigarettes and e-cigarettes.102

Research in the US has shown HTPs were likely to appeal to adolescents and young adults.103104 A national survey found 0.7% of middle and high school students reported using a HTP in the past 30 days.105

HTP use is markedly higher across Europe, and rising. A 2017-18 survey found 1.8% of participants from 11 European countries had ever used a HTP (the highest figure in Greece) and 0.1% were current users.106 2020 data from 28 European countries found 6.5% had ever used a HTP (the highest being nearly 15% in Czech Republic) and 1.3% were current users.107 Both these studies also noted HTP use was more common among younger people, and former and current smokers.

A study across Canada, England and the US found that, on average, in 2017, 7% of 16- to19-year-olds reported awareness of IQOS with the highest figure in the US. The same study found that around 40% expressed an interest in trying IQOS.108

Similarly to the Western Pacific Region, the 2023 systematic review mentioned above found use of HTPs significantly increased in the European Region between 2015 and 2022.101 The authors found this was the case for lifetime, current and daily use of HTPs. HTP use in the region of the Americas did not significantly change.101

Take up supported by favourable taxation?

In Europe, Italy was at the forefront of HTP developments. PMI chose Milan to trial IOQS reportedly due to beneficial tax treatment of the product by the Italian government (50% lower than conventional cigarettes, and at the same level as e-cigarettes) as well as more lenient packaging and marketing regulations.109110111 Research from Italy indicated that PMI’s annual sales of IQOS grew from 11 tonnes in 2015, to 83 tonnes in 2016, and 519 tonnes in 2017.110 In contrast, in July 2017, BAT Chief Executive Nicandro Durante reported that BAT had seen “no success whatsoever” with glo in European markets like Italy and Switzerland.29 By 2019, BAT appeared to have had a little more success in Italy, but PMI continued to dominate.86

The FCTC requires that HTPs are taxed as tobacco products, but they are taxed more favourably than cigarettes in a number of countries (see The Campaign for Tobacco Free Kid’s web pages on global tobacco taxation). It is not clear if this always results in lower prices for the consumer, and how this relates to consumption and adoption rates. A research study in 2018 concluded that: “The tax advantages being given to HTPs may instead of providing a price signal to a consumer looking to switch, be providing a profit signal to tobacco companies to switch over to selling more HTPs and fewer combusted cigarettes”.112

In 2020, the European Commission announced a review of tax rates for HTPs and e-cigarettes, with a view to achieving harmonisation of product definitions and taxation. The consultation phase was announced on 2 June, and intense lobbying for the tobacco industry was anticipated.113114115 The US based Tax Foundation, a think tank with tobacco industry links, published an article the next day detailing existing tax rates in Europe and outlining proposals for change.116

Harm Reduction: A Tobacco Solution to a Tobacco Problem?

Tobacco companies frame HTPs as less harmful alternatives to cigarettes, while the WHO continues to urge caution, stating that independent scientific evidence does not bear out these claims.

Research on heated tobacco products (HTPs) is less developed than that relating to e-cigarettes.117118 The general independent scientific consensus is that when smokers switch fully from conventional cigarettes to HTPs, they are exposed to reduced levels of some harmful substances.119 However, HTP users are also exposed to higher levels of other potentially harmful substances and the subsequent risks of harm, especially after long-term use, remain unknown.11954There is also no reliable evidence that they help people stop smoking cigarettes.119

The UK Cochrane review, published in January 2022, noted that to date all randomised control trials (RCTs) assessing the safety of HTPs had been funded by tobacco companies. Of the eleven trials eight were “at unclear risk of bias and three at high risk”.119 The Cochrane reviewers concluded that: “Independently funded research on the effectiveness and safety of HTPs is needed.”119

The Industry Narrative

RJ Reynolds’s executive Steven Alderman testified in an American court in 2016 that there is no such thing as a ‘safe’ tobacco product.120 Yet, some tobacco manufacturers have marketed HTPs with direct and indirect claims that they are less toxic or less harmful than conventional cigarettes.121122123

BAT and PMI have set up dedicated websites (bat-science.com, pmiscience.com) to showcase their harm reduction efforts, and have published some of their findings in scientific journals.12412590126127

On 7 July 2020, the FDA partially approved PMI’s MRTP application.54 Immediately after the FDA’s decision, PMI launched an international PR campaign, calling it a “public health milestone” (see below).54128 PMI stated that they intended to pursue full approval, and that the FDA had “left the door open to continue the dialog with them on precisely the next level”.129

Although BAT indicated that it would undertake similar regulatory steps with glo, as of January 2023, BAT had not submitted an application to the FDA.29

Emerging Independent Evidence

Public health advocates have cautioned that the short and long-term health effects of HTPs remain unclear, and that due to the tobacco industry’s long history of deceit over the health risks of smoking,130 there is an urgent need for independent evidence.131132133

According to the World Health Organization (WHO):

“this generation of HTPs has not been on the market long enough for potential effects to be studied. Conclusions cannot yet be drawn about their ability to assist with quitting smoking (cessation), their potential to attract new youth tobacco users (gateway effect), or the interaction in dual use with other conventional tobacco products and e-cigarettes. Future independent studies should address these effects, as well as the safety and risk of HTPs.”2

A new body of evidence is emerging that suggests that HTPs may be more harmful to health than tobacco companies would like us to believe. In May 2017, Auer and colleagues published a research letter in JAMA Internal Medicine which challenged PMI’s claim that IQOS heats tobacco without combustion, fire, ash, or smoke, and accused the company of “dancing around the definition of smoke to avoid indoor-smoking bans”.134 According to the authors, PMI has misappropriated the popular, yet scientifically incorrect, perception that combustion releases harmful chemicals and creates smoke. Rather, the authors argue, incomplete combustion (a chemical process known as ‘pyrolysis’) can also produce cancer-causing chemicals. Importantly, the authors demonstrate that pyrolysis occurs in IOQS.134 PMI acknowledges this in its own research.135

In line with this, a 2022 review by independent researchers found that emissions from IQOS could be defined as both aerosol and smoke, and that smoke can arise without combustion. Further, the existing evidence confirms that IQOS releases potentially harmful chemicals, albeit at lower levels than cigarettes on a per stick basis. However, the researchers go on to explain that PMI’s studies may underestimate the yields of harmful chemicals in IQOS emissions. When comparing levels based on tobacco mass in each product, IQOS emits roughly twice as much tar and nicotine compared to cigarettes.136

In December 2017, following concerns raised by former PMI employees and contractors over “a number of irregularities” involving clinical trials that underpin PMI’s application to the FDA.137 Reuters conducted an independent investigation. They found PMI had dropped one particular experiment because the basic procedure for obtaining informed consent from trial participants had not been followed. Speaking to the investigator in charge of that particular experiment, Reuters was told that he “knew nothing about tobacco”. Reuters also reported that a second investigator had submitted urine samples exceeding human levels, and a third had told Reuters that he “doesn’t hold such company-sponsored clinical trials in high regard, describing them as ‘dirty’ because their purpose is more commercial than scientific”.137 PMI’s response to the Reuters report was that “all studies were conducted by suitably qualitied and trained Principle Investigators”, and that PMI had “taken steps to address any reported irregularities in our studies”.137

In 2018, researchers at the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) published their research into PMI’s HTPs.30 They reviewed leaked internal industry documents relating to the IQOS “precursor” Accord as well as contemporary company documents and communications, and PMI’s MRTP application. They found that:

“PM marketed Accord as a ‘cleaner’ tobacco product in an attempt to address smokers’ growing health concerns without making explicit health claims. While PM communications asserted that Accord reduced users’ exposure to harmful constituents, company scientists and executives consistently stressed to both regulators and the public that such reductions did not render Accord safer.”30

Their research showed that the design of IQOS (and its marketing statements) were similar to those for Accord, and therefore IQOS was a new product variant, but “without consistent improvements in exposure to aerosol toxic compounds”.30 They concluded that:

“In contrast to PM’s past claims for Accord, PMI now claims in its MRTP application that IQOS reduces health risk. This shift in stance is likely not the result of any toxicological difference between Accord and IQOS, but rather a change in the social and regulatory landscape permitting these claims.”30

An analysis of IQOS commissioned by the Italian Government also concluded that PMI’s reduced risk claims did not hold up. An investigation in 2020 by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and Italian broadcaster Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) found that Italy’s National Health Institute had conducted analysis on HTPs, after being approached by PMI.138139140 The Institute reported its findings to the Italian government after a reduction in tax on HTPs (to 50% of that of combustible cigarettes) had been approved by parliament.139141

In early June 2020, Italy’s Health Ministry released a summary of this research which concluded that:

“The scientific data presented … is not enough to establish that [IQOS] reduces the risk of the product compared to combustion products with the same conditions of use” (translated by OCCRP from Italian).139

PMI itself stated in its MRTP application to the FDA that:

“It has not been demonstrated that switching to the IQOS system reduces the risk of developing tobacco-related diseases compared to smoking cigarettes”.54142

The 2020 TCRG/STOP briefing provides a more detailed, but accessible, explanation and critique of the FDA’s authorization of IQOS as an MRTP.54

A Cochrane review published in January 2022, found very limited data on the effectiveness of HTPs as smoking cessation aids and thus concluded their use to help smokers quit remains uncertain. The authors did identify two time-series studies, which showed an accelerated decline in cigarette sales following the introduction of HTPs to the Japanese market. However the authors went on to explain “[t]his evidence was of very low‐certainty as there was risk of bias, including possible confounding, and cigarette sales are an indirect measure of smoking prevalence.”119

Threat to Implementation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

The WHO and the Secretariat to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) have warned that the tobacco industry’s HTPs are addictive,143 “in pursuit of profit rather than public health”,144 and should be subjected to the same policy and regulatory measures applied to all tobacco products, in line with the FCTC.143

Regulation of HTPs

At the FCT Conference of the Parties in 2018 (COP 8), the parties agreed to regulate HTPs as tobacco products under the FCTC Articles and guidelines.145 In March 2019, the Secretariat of the WHO FCTC issued an information note, which compiled all Conference of the Parties (COP) decisions related to novel tobacco products, including HTPs.146

Individual countries are at different stages in their regulation of HTPs; some have banned them outright, while some in Europe have allowed their sale under certain regulatory conditions.147148149 For more information see the webpages for the Policy Scan Project, by the Institute for Global Tobacco Control (at Johns Hopkins University), which tracks and reports regulatory approaches to heated tobacco products (HTPs) around the world.

There were some significant changes to regulation in the late 2019 and early 2020. In December 2019, India passed a law banning HTPs, e-cigarettes and all similar devices.150 In February 2020, Mexico banned the import of HTPs and e-cigarettes by Presidential Decree.151 In June 2020, the Australian government’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) made an interim judgement rejecting the sale of HTPs, which became final in August 2020, in the face of considerable lobbying from PMI to allow the sale of IOQS in Australia.152153154155 The TGA concluded in its final judgement that:

“maintaining the current scheduling for HTPs is necessary to protect public health from the risks associated with introducing a new nicotine product for non-therapeutic use.”153

In September 2019, the FCA Secretariat released a statement urging governments to remain vigilant towards emerging nicotine and tobacco products.156 Tobacco control researchers have pointed out “there is nothing in US law or the FCTC that prevents authorities from prohibiting HTPs”.52

EU ban on characterising flavours

HTPs were initially exempted from the EU ban on characterising flavours in tobacco products. However, after sales of HTPs had increased significantly in members states a ban was implemented in 2023. This is likely to be challenged in the European Court of Justice.157 For details see Menthol Cigarettes: Industry Interference in the EU and UK

PMI Promotion of HTPs

Even before the FDA granted IQOS “modified exposure” status, there was evidence of PMI promoting their HTP as a reduced risk product outside the US, where regulations on marketing are less stringent.123147158159 The TCRG/STOP briefing identifies the potential for misrepresentation of the partial approval applying to the marketing of IQOS in the US.54 Research from the US in 2020 anticipated PMI’s promotional tactics, concluding that “reduced exposure claims as well as reduced risk claims on PMI’s IQOS product packaging are likely to mislead consumers, especially youth, and thereby endanger public health.”104

On 27 July 2020, the WHO issued a statement reminding parties that “Heated tobacco products are tobacco products” and that, while the US is not a signatory, where countries are signed up to the FCTC, it fully applies to HTPs.160 In relation to health impacts, it stated:

“WHO reiterates that reducing exposure to harmful chemicals in Heated Tobacco Products (HTPs) does not render them harmless, nor does it translate to reduced risk to human health. Indeed, some toxins are present at higher levels in HTP aerosols than in conventional cigarette smoke, and there are some additional toxins present in HTP aerosols that are not present in conventional cigarette smoke. The health implications of exposure to these are unknown.(…) Given that health may be affected by exposure to additional toxins when using HTPs, claims that HTPS reduce exposure to harmful chemicals relative to conventional cigarettes may be misleading.”160

The WHO also drew attention to the FDA’s specific conditions requiring monitoring of youth use and exposure, and that PMI must not use the FDA decision to mislead consumers:

“Even with this action, these products are not safe nor “FDA approved.” The exposure modification orders also do not permit the company to make any other modified risk claims or any express or implied statements that convey or could mislead consumers into believing that the products are endorsed or approved by the FDA, or that the FDA deems the products to be safe for use by consumers.”160161

In 2020 PMI began quoting the FDA decision in its press releases and media interviews around the world, pushing for a greater acceptance of IQOS, more favourable regulation of HTPs, and to allow their introduction in countries where they are currently, or soon to be, banned. For example, in Hong Kong, various media outlets have published articles in which the FDA decision has been used to advocate against a proposed ban on newer products.162163

On 1 September 2020 the Mexican Ministry of Health made a public statement referring to PMI’s “aggressive” campaign for IQOS in Mexico, including its misleading use of the FDA decision.164 This statement reiterated the ban on the import of HTPs, and made clear that the Mexican government had not granted IQOS any form of reduced risk status, and that it did not support its use as a tool to stop smoking. It also confirmed that, while the product was already being marketed in Mexico, doing so remained illegal. The Ministry of Health reaffirmed the WHO position; that HTPs are tobacco product, and should be regulated as such, and that any interference in public health by the tobacco industry should be resisted.164

- For more details go to PMI Promotion of IQOS Using FDA MRTP Order.

Bath TCRG researchers, in an editorial published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in September 2020, warned that the FDA’s decision was likely to lead to “regulatory confusion” in respect of HTPs.165 They reiterated the WHO recommendation to regulate HTPs as tobacco products, and urged the FDA to “make its terminology clearer to ensure products which meet only reduced exposure criteria cannot be misrepresented as reduced harm”.165

PMI has made a number of attempts to promote IQOS to governments as a cessation tool, supported by its own estimates of IQOS use. It downplays the evidence on dual use with cigarettes and the potential for uptake by non-smokers including youth.

- For details see: PMI’s IQOS: Use, “Quitting” and “Switching”.

Patent Challenges

BAT and PMI have made legal claims against each other in multiple jurisdictions around the world, in relation to patents for the tobacco heating technology in IQOS and glo.166167

A court ruling in 2021 limited Altria’s distribution of PMI’s IQOS in the US,168 and the US International Trade Commission banned the import of IQOS.169170171172 Another ruling in 2022 ordered RJ Reynolds (BAT’s subsidiary) to pay PMI $10.7 million.173

In February 2024 BAT and PMI announced that they had reached a settlement to resolve “all ongoing patent infringement litigation between the parties related to our heated tobacco and vapour products.”174175173 The companies stated that this settlement allowed “each party to innovate and introduce product iterations.”174175 As part of the settlement, PMI and BAT will jointly request the ban on IQOS imports be revoked.173

Relevant Links

- WHO information sheet on Heated Tobacco Products (2nd Edition)

- Addiction at any cost: Philip Morris International Uncovered, Stopping Tobacco Organisations and Products/Tobacco Control Research Group, 2020

- STOP/TCRG, FDA does not rule that IQOS reduces tobacco-related harm, yet PMI still claims victory, Issue brief, July 2020

- WHO statement on heated tobacco products and the US FDA decision regarding IQOS, July 2020

TobaccoTactics Resources

- Heated Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International

- Newer Nicotine & Tobacco Products: Japan Tobacco International

- Newer Nicotine & Tobacco Products: British American Tobacco

- Newer Nicotine & Tobacco Products: Imperial Brands

- Harm Reduction

TCRG Research

- Critical appraisal of interventional clinical trials assessing heated tobacco products: a systematic review, Braznell S, Van Den Akker A, Metcalfe C, G.M.J. Taylor, J. Hartman-Boyce, Tobacco Control, Published Online First: 08 November 2022, doi: 10.1136/tc-2022-057522

- Tobacco industry messaging around harm: Narrative framing in PMI and BAT press releases and annual reports 2011 to 2021, I. Fitzpatrick, S. Dance, K. Silver, M. Violini, T.R. Hird, Frontiers in Public Health, 18 October 2022. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.958354. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3528

- US regulator adds to confusion around heated tobacco products, A.B. Gilmore, S. Braznell, BMJ, 2020;370:m3528

- Understanding the emergence of the tobacco industry’s use of the term tobacco harm reduction in order to inform public health policy, S. Peeters, A. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2015,24(2):182-189. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051502