Philip Morris International

This page was last edited on at

Background

Philip Morris International (PMI) is the largest tobacco company in the world (excluding the Chinese National Tobacco Corporation).1 The company is headquartered in New York in the United States (US), but also based operationally in Lausanne, Switzerland and Hong Kong. According to the Associated Press, Altria decided to separate Philip Morris USA and its international operations in order to “clear the international tobacco business from the legal and regulatory constraints facing its domestic counterpart, Philip Morris USA”.2

In 2018, PMI and its subsidiaries sold its products in over 180 markets, selling cigarettes, other tobacco products and newer nicotine and tobacco products. The company reported in 2019 that it held 28.4% of the global market for cigarette and heated tobacco products (HTPS) excluding the US and China.3 The company owned six of the top 15 international cigarette brands in 2018. Its global cigarette brands are Marlboro (the world’s bestselling international brand), Merit, Parliament, Virginian S, L&M, Philip Morris, Bond Street, Chesterfield, Lark, Muratti, Next and Red & White. The company reported owning a market share of at least 15% or over in 100 countries in 2018, although in the UK PMI held only fourth position for cigarette market share behind Imperial Tobacco, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) and British American Tobacco (BAT).4

According to Euromonitor International, PMI’s global share of the cigarette market (by retail volume) was under 14% in 2018, and fell to 12% in 2020 (figures rounded). 5

On 27 August 2019, global news outlets reported that PMI and Altria were considering a merger to reunite the brands that had split in 2007.678 However the merger was called off the next month, in response to news that the FDA was considering a ban on flavoured e-cigarettes.910 On March 21, 2018, PMI acquired Tabacalera Costarricense, S.A. and Mediola y Compañía, S.A. for USD$95 million, which sell Derby, Marlboro and L&M cigarettes in Costa Rica.3

Employees or Board Members: Past and Present

Jacek Olczak was appointed the Chief Executive Officer of PMI in May 2021.11 Previously he was the company’s Chief Operating Officer. He succeeded André Calantzopoulos who was appointed Executive Chairman of the Board. The previous chairman Louis C. Camilleri, stepped down in Decemer 2020. A full list of the company’s leadership team can be accessed at PMI’s website. Other persons that currently work for, or have previously been employed with, the company:

Massimo Andolina | Chris Argent | Drago Azinovic | Emmanuel Babeau | Werner Barth | Charles Bendotti | Frank de Rooij | Frederic de Wilde | Suzanne Rich Folsom | Stacey Kennedy | Martin King | Michael Kunst | Andreas Kurali | Bin Li | Marco Mariotti | Mario Massroli | Deepak Mishra | Silke Muenster | John O’Mullane | Paul Riley | Marian Salzman | Gregoire Verdeaux | Michael Voegele | Stefano Volpetti | Jerry Whitson | Martin J. Barrington | David Bernick | Bertrand Bonvin | Harold Brown | Patrick Brunel | Mathis Cabiallavetta | Louis C. Camilleri | Andrew Cave | Herman Cheung | Kevin Click | Marc S. Firestone | John Dudley Fishburn | Jon Huenemann | Even Hurwitz | Jennifer Li | Graham Mackay | Sergio Marchionne | Kate Marley | Kalpana Morparia | Jim Mortensen | Lucio A. Noto | Matteo Pellegrini | Robert B. Polet | Ashok Rammohan | Carlos Slim Helú | Julie Soderlund | Hermann Waldemer | Stephen M. Wolf | Miroslaw Zielinski

Affiliations

Memberships

In 2019, PMI declared membership of the following organisations on the European Transparency Register:12

The American Chamber of Commerce to the European Union | American European Community Association (AECA) | American Chamber of Commerce of Lithuania | Ass. Industrial Portuguesa (AIP) | Business Europe | Centromarca | CEOE | Czech Association Branded Goods | Czech Foodstuff Chamber | Economiesuisse | Estonian Chamber of Commerce | European Communities Trademark Association (ECTA) | European Policy Centre (EPC) | Kangaroo Group | Latvian Chamber of Commerce | Latvian Traders Association | Lithuanian Confederation of Industrialists | MARQUES | Spanish Tobacco Roundtable | VBO-FBE

PMI had previously listed memberships of: International Trademark Association (INTA) | The Trans-Atlantic Business Council (TABC) | | European Risk Forum | European Smokeless Tobacco Council (ESTOC) | British Chamber of Commerce | Public Affairs Council | APRAM | LES France | AmCham Germany | Bund fur Lebensmittelrecht & Lebensmittelkunde | Europaischer Wirtschaftssenat (EWS) | Wirtschaftsbeirat der Union e.V. | American Chamber of Commerce of Estonia | American Lithuanian Business Council | Lithuanian Confederation of Industrialists | Investors’ Forum | AmCham Spain | Unindustria (Confindustria) | Consumer Packaging Alliance | British Brands Group | Foodstuff Chamber The company is also a donor to the Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing Foundation (ECLT), alongside BAT, Imperial Brands, JTI and Swedish Match, among others.13

In May 2015, ECLT and the International Labour Organization (ILO) entered into an agreement to develop global guidance on occupational health and safety with regards to child labour in the tobacco industry.14 PMI was a member of the Confederation of European Community Cigarette Manufacturers (CECCM), but left in 2006 following a dispute with other members.15

Consultancies

PMI has worked with numerous Public Relations (PR) and law consultancies:

- In 2020 and 2021 PMI released white papers and held events on public trust in science in partnership with the Industry Transformation Coalition.

- In January 2020, PMI released a white paper entitled “Unsmoke Your Mind: Pragmatic Answers to Tough Questions for a Smoke-Free Future”. The company enlisted the consulting firm Povaddo, which works across public affairs, strategy and research,16 to conduct an opinion-based survey of smokers across 14 countries.17 The report was heavily criticised in The Lancet medical journal (see below)18 who pointed out that its findings were based on a “self-funded online survey”.18 In July 2020, PMI published another white paper called “In Support of the Primacy of Science”, which was also based on online surveys conducted by Povaddo, on the public’s views on science.1920 In March 2021 PMI released the results of a third online survey, conducted by Povaddo in 20 countries, on public attitudes to newer nicotine and tobacco products and collaboration between governments and tobacco companies.21 Povaddo has conducted previous research for PMI.22

- In December 2019, researchers and academic institutions received invitations from the consulting firm, Handshake, to commission research on behalf of PMI on how companies navigate corporate transformation.23

- In 2016, Philip Morris UK was a client of London-based PR and communications company Instinctif Partners.

- That same year, media also linked Brussels-based PR company Pantarhei Advisors to Philip Morris.

- In 2014, UK-based Media Intelligence Partners was PMI’s media contact during Sir Cyril Chantler’s plain packaging review.

- In 2014, German PR company Communications & Network Consulting AG (CNC) listed Philip Morris as a client on the EU Transparency Register.

- In that same year, Luxembourg-based Felula SA, a one-person consultancy run by Serge Estgen, listed PMI as its client on the EU Transparency Register.

- In 2013, Edinburgh-based Halogen Communications supported PMI’s opposition to Scotland’s plans to introduce Plain Packaging.

- In 2012 and 2013, PMI worked with London-based PR and media company Pepper Public Affairs on PMI’s Anti-Plain Packaging Media Campaign.

- In 2012, the UK branch of Crosby Textor Group, helped PMI oppose Plain packaging in the UK.

- Law firm Clifford Chance has a history of lobbying for PMI in the UK and European Union (EU). In 2009, the firm submitted anonymous Freedom of Information requests to a UK university on behalf of the tobacco company, and in 2011 and 2012 Clifford Chance’s Michel Petite lobbied on the EU Tobacco Products Directive.

- From 2009 to 2011 PR company Gardant Communications worked for Philip Morris UK. In 2009, the PR company supported Philip Morris’ PR Campaign Against the Display Ban and was involved in Philip Morris’ Regulatory Litigation Action Plan Against the Display Ban.

- APCO Associates‘ collaboration with PMI goes back to the 1990s when it helped the company set up the European Science and Environment Forum. More recently, it was involved in Philip Morris’ PR Campaign Against the Display Ban.

- London-based PR company INHouse Communications also played a part in Philip Morris’ PR Campaign Against the Display Ban.

- Ogilvy Group‘s collaboration with Philip Morris goes back to the 1950s when it ran one of its advertising campaigns.

- José María Aznar, the former Spanish Prime Minister (see below)

Controversial Marketing Strategies

Since its controversial “Be Marlboro: Targeting the World’s Biggest Brand at Youth” campaign in 2014, PMI have been accused on multiple occasions of targeting their products at young people. On its website, PMI says that it is “committed to doing our part to help prevent children from smoking or using nicotine products”. 24 It further states that its “marketing complies with all applicable laws and regulations, and we have robust internal policies and procedures in place so that all our marketing and advertising activities are directed only toward adult smokers”.24 Despite these assurances, PMI has been accused of, and fined for, running marketing campaigns that target young people. For more information see Be Marlboro: Targeting the World’s Biggest Brand at Youth. PMI has increasingly used social media to market its newer products, including e-cigarettes (also known as electronic nicotine delivery systems, or ENDS) and heated tobacco products.

- For more information on PMI’s newer, including IQOS, visit Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International and Heated Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International.

In December 2023 The Times newspaper highlighted PMI’s role in third party campaigns promoting e-cigarettes in the UK.25 For more information visit the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World page.

Complicity in Tobacco Smuggling

PMI portrays itself publicly as a victim of illicit tobacco trade, with the company reporting that tobacco smuggling results in “considerable financial losses” and “damage” to manufacturers’ brands.26 To help tackle illicit trade, PMI launched a funding initiative called PMI IMPACT in 2016, worth US$100m and aimed at bringing together “organisations that fight illegal trade and related crimes, enabling them to implement solutions”.2728 In its first call for proposals in 2016, PMI asked for “projects that have an impact on illegal trade and related crimes in the European Union…”29 The second call, made in 2017, expanded the areas of focus to include the Middle East, North Africa, South and Central America and South and Southeast Asia.30 For more information, visit our page on PMI IMPACT. In contrast to the company’s public persona of being part of the smuggling solution, evidence shows that the company was, in fact, part of the problem. In 2000, the European Commission (backed by a majority of EU member states) started court proceedings in the US Courts against PMI and other tobacco companies for its complicity in tobacco smuggling. The Commission claimed that the tobacco companies “boosted their profits in the past by deliberately oversupplying some countries so that their product could be smuggled into the EU”, costing the EU millions of euros in lost tax and customs revenue.3132 PMI and the Commission settled their dispute in 2004, when the company agreed to pay the Commission £675m to fund anti-smuggling activities.33 The two Parties signed an Anti-Counterfeit and Anti-Contraband Cooperation Agreement,34 referred to by the company as Project Star. As part of this agreement, PMI commissioned KPMG to measure annually the size of the legal, contraband and counterfeit markets for tobacco products in each EU Member States. Project Star’s methodology and data have been strongly criticised for lack of transparency, overestimating illicit cigarette levels in some European countries, and serving PMI’s interests over those of the EU and its member states.35

Tactics to Subvert Tobacco Control Campaigns and Policies

PMI has strongly opposed tobacco control legislation and regulations across the world, including plain packaging in Australia and the UK, the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), and tobacco control decrees in Uruguay. The company has used a variety of strategies and tactics to influence tobacco control policies and subvert existing regulations.

Funding Pro-Tobacco Research and Discrediting Independent Evidence

In response to plain packaging proposals in the UK, PMI funded research, expert opinion and public relations activities which supported its position. One of the people that PMI funded for this purpose was Will O’Reilly, a former Detective Chief Inspector with the London Metropolitan Police. O’Reilly was appointed as a PMI consultant in 2011,36 conducting undercover test purchases of illicit tobacco and publicising his findings in UK regional press.37 One of PMI’s arguments to oppose plain packaging was that the public health measure would lead to an increase in illicit tobacco, including counterfeited plain packs. For background on, and a critique of, this argument, go to Countering Industry Arguments Against Plain Packaging: It will Lead to Increased Smuggling. O’Reilly’s test purchases appear to have enabled PMI to secure significant press coverage of its data on illicit tobacco.38 In March 2019, Euromonitor International, a market research organisation, received funding through two PMI initiatives: the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World and PMI IMPACT.394041 Examples of other organisations and individuals that have received funding from PMI to produce research or expert opinions or critiques of independent evidence, in order to oppose tobacco control legislation are: Deloitte | KPMG | Transcrime | Roy Morgan Research | Ashok Kaul | Michael Wolf | Populus | Centre for Economics and Business Research4243 | Compass Lexecon44 | Rupert Darwall45 | James Heckman46 | Lord Hoffman47 | Alfred Kuss48 | Lalive 49 | LECG505152 | London Economics | Povaddo22| SKIM Consumer Research53

- To see a list of all organisations funded through PMI’s Foundation for a Smoke-Free World (FSFW), visit our pages on the FSFW’s Centres of Excellence and grantees.

- For more information on the tobacco industry’s use of research to undermine legitimate independent evidence see: Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Funded Research, Expert Opinion and Public Relations.

Using Freedom of Information Requests to Acquire Public Health Research Data

Freedom of Information (FOI) requests are one strategy that the tobacco industry uses to undermine tobacco control legislation, often covertly using third parties.54 In 2009, and again in 2011, PMI sent Freedom of Information requests to Stirling University (UK) requesting access to a wide range of data from its research on teenage smoking. PMI alleged that it wanted “to understand more about the research project conducted by the University of Stirling on plain packaging for cigarettes”.55 The FOI requests were eventually dropped. For more information on these FOI requests, and an explanation on how these requests impacted the University of Stirling, go to our page FOI: Stirling University.

Fabricating Support through Front Groups

PMI has used front groups to oppose tobacco control measures. Front Groups are organisations that purport to serve a public interest, while actually serving the interests of another party (in this case the tobacco industry), and often obscuring the connection between them. In Australia, leaked private documents revealed that the supposed anti-plain packaging retailer grass roots movement, the Alliance of Australian Retailers was set up by tobacco companies and that the Director of Corporate Affairs Philip Morris Australia, Chris Argent, played a critical role in its day-to-day operations.565758

- For more information on this front group, and Philip Morris Australia’s involvement, visit the Alliance of Australian Retailers page.

- For more information on front groups funded and/or organised by PMI and other tobacco companies, see the list on the Expose Tobacco website.

Lobbying of Decision Makers

Article 5.3 of the The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) explicitly aims to reduce industry influence in public health policymaking by obliging parties to protect their health policies from tobacco industry interests and interference.59 Yet tobacco industry representatives, and third-parties regularly attempt to influence public health policymaking in the industry’s favour. This section details some of these incidents involving PMI and the response of the governments and the global health community.

EU

PMI reported that it spent between €1,250,000 and €1,499,999 in 2019 lobbying EU institutions, employing only 2 fulltime equivalent staff in its Brussels office.12 If this data is correct, it suggests that PMI relied heavily on external lobbying firms. A 2013 leaked internal PMI document revealed that the company had 161 lobbyists working to undermine the revision of the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD).60 The objective of PMI’s campaign was to either “push” (i.e. amend) or “delay” the TPD proposal, and “block” any so-called “extreme policy options” like the proposed point of sales display ban and plain packaging.61

- For more information on PMI’s campaign to undermine the TPD, go to EU Tobacco Products Directive Revision and PMI Mobilised Support from Retailers.

UK

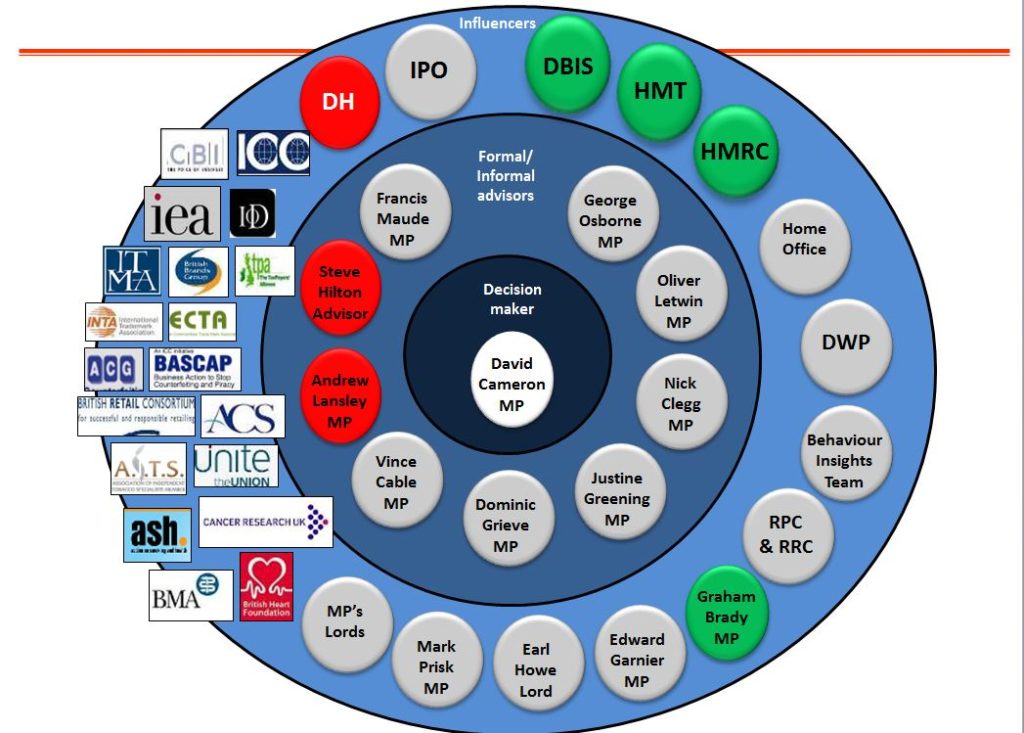

The leaked internal PMI documents from 2013 also revealed the extent of a multi-faceted campaign against Plain Packaging in the UK, including a detailed media campaign using dozens of third parties (both individuals and organisations) to promote its arguments against the policy. The documents also included a detailed political analysis of potential routes of influence for the tobacco company (Image 1).36

One third party appointed in November 2011 to help PMI oppose the plain packaging proposal was the Crosby Textor Group. This appointment led to a conflict of interest scandal, given that Lynton Crosby co-Director of the Crosby Textor Group, was also the political election strategist for the UK’s Conservative Party, which was in power in the UK. David Cameron, then Prime Minister, insisted that Crosby never lobbied him about plain packaging. 6263 Despite a lack of evidence that Crosby lobbied the Prime Minister and Health Minister on plain packaging, documents released under FOI legislation, obtained by the University of Bath Tobacco Control Research Group, show that Crosby lobbied the UK Government on plain packaging via Lord Marland, the then Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Intellectual Property, to oppose plain packaging. For more information on this lobbying scandal, go to Lynton Crosby’s page.

- For more detail on PMI’s attempts to undermine plain packaging proposals in the UK, visit: PMI Mobilised Support from Retailers | PMI’s Anti-Plain Packaging Lobbying Campaign | PMI’s Anti-Plain Packaging Media Campaign | PMI’s “Illicit Trade” Anti-Plain Packaging Campaign

- For information on the tobacco industry’s tactics to undermine this tobacco control measures, visit our pages on: Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Company Opposition | Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Funded Research, Expert Opinion and Public Relations | Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Built Alliances | Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Funded Third Party Campaigns

- PMI also opposed the tobacco product display ban gradually introduced in the UK from 2012. More information on PMI’s tactics to stop this measure, see: Philip Morris’ PR Campaign Against the Display Ban

Australia

Australia has one of the least hospitable regulatory environments for the tobacco industry, having passed regulations banning advertising since 1976, a point of sale ban in 2011, and a plain packaging law in 2012. It also has regulation in place to prevent the sale of nicotine products, including e-cigarettes and HTPs.64

The industry has not, however, given up on attempting to market its products and lobby decision makers across the country. In a 2019 article, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that Tammy Chan, Managing Director of PMI Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific wrote letters to health organisations urging them to enter into a “dialogue” on PMI’s “smoke-free” vision in the lead up to a parliamentary select committee meeting on the impact of e-cigarettes on “personal choice”.65

In March 2019, PMI was accused of “subliminal advertising” in its sponsorship of the Ferrari Formula One team during the Australian Gran Prix in Melbourne. PMI has been accused of attempting to evade advertising bans by sponsoring motorsports teams.

- For more information see Motorsport Sponsorship

Latin America

José María Aznar, the former Prime Minister of Spain, has been widely reported by media outlets as having taken up a position as a lobbyist for PMI in Latin America.66676869

- For more information on his meetings with public officials in Chile and Peru, as well as his history of association with the tobacco industry while in office, see our page on José María Aznar.

Intimidating Governments with Litigation or Threat of Litigation

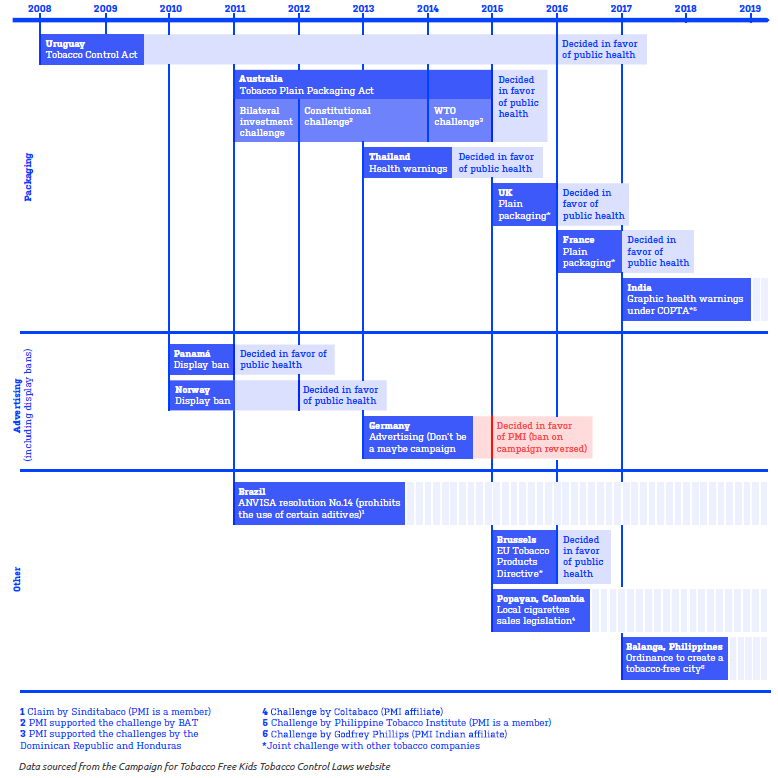

PMI has legally challenged tobacco control regulations across the globe, including:

- Comprehensive No Smoking Ordinance (2010 and 2016) and Tobacco-Free Generation Ordinance (2016) in Balanga, Philippines. A front group for the world’s biggest tobacco companies, including PMI, called the Philippine Tobacco institute (PTI) sued the city of Balanga in August 2017 over the Comprehensive No Smoking Ordinance, which it argued was “arbitrary and oppressive” and cost PMI USD$420,000 a month in lost sales. In July 2018, regional courts ruled in PTI’s favour, noting that although the city’s tobacco control efforts were “commendable”, they were also unconstitutional. PTI launched another lawsuit in May 2018 to challenge the constitutionality of the city’s Tobacco-Free Generation Ordinance.65

- The Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Packaging and Labelling) Second Amendment Rules, 2018 text and pictorial health warnings law in India. PMI affiliate Godfrey Phillips India sought a stay of implementation of new legislation requiring health warnings to increase to cover 85% of the surface of cigarette packaging, from the High Court of Karnataka in Bangalore, India. The Court rejected the request for stay in August 2018. The legality of the Rules themselves was at the time pending in the Supreme Court.71

- The May 20, 2016 Decree plain packaging law in France. In December 2016, the Conseil d’Etat (the Council of State, the highest administrative jurisdiction in France) dismissed a six-part legal challenge jointly brought against the plain packaging law by JTI, Philip Morris France, BAT France, a tobacco paper manufacturer and The National Confederation of Tobacco Retailers of France (Confédération Nationale des Buralistes de France).72

- In 2013, the mayor of Popayán, a city in southwestern Colombia, issued a decree prohibiting tobacco sales within 500 metres of schools, libraries and health institutions. Following heavy lobbying from Coltabaco, a Philip Morris affiliate, the radius was decreased to 200 metres. Coltabaco sued Popayán in March 2015, arguing that a mayoral decree was insufficient to effect legitimate regulation. Coltabaco won its lawsuit in September 2015.73

- The Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Regulations 2015 (UK). Following the passage of the legislation in March 2015, PMI and others launched a legal action, which it lost in May 2016 (the day before the legislation was due to come into force).7475

- The 2014 EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD). PMI and BAT attempted to invalidate the TPD as a whole, or various provisions within it, but this legal challenge was dismissed in the European Court of Justice in May 2016.76 More details can be found on the page TPD: Legal Challenges.

- The Ministry of Public Health Notice of Rules, Procedures, and Conditions for the Display of Images, Warning Statements, and Contact Channels for Smoking Cessation on Cigarette Labels of 2013 (Thailand). In July 2013, Philip Morris Thailand and Japan Tobacco International (JTI) Thailand requested a temporary injunction against an increase of picture and text health warnings from 55 to 85 percent of the front and back of cigarette warnings. Though their request was initially granted in August 2013 in the Central Administrative Court of Thailand, the injunction was reversed in May 2014 by the Supreme Administrative Court following appeal by the government. PMI and JTI ultimately withdrew their legal challenge.77

- Following heavy criticism of its “Be Marboro” campaign worldwide (see below), Germany banned PMI from displaying “Be Marlboro” advertising in the country. A German court overturned the ban in 2015, stating that the wording of the advertisements did not explicitly target younger than legal age smokers.78

- National Systems of Health Oversight RDC No. 14/2012 Brazil. The Brazil Health Regulatory Agency’s (ANVISA) resolution No. 14 banned tobacco additives and flavours. The National Confederation of Industry (Confederação Nacional da Indústria) challenged the ban as an unconstitutional use of regulatory power. In February 2018, the highest court in Brazil, the Supreme Federal Tribunal, upheld the 2012 ban and reaffirmed the right of ANVISA to regulate tobacco products.79

- The Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Australia). PMI fiercely opposed the legislation, fearing that it might set a global precedent. The company fought this legislation unsuccessfully on three fronts:

- World Trade Organization (WTO) challenge: In 2014, PMI supported a request by the Dominican Republic government before the WTO Dispute Settlement Body, alleging that Australia’s plain packaging laws breach the WTO’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) and agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).80 Similar requests were submitted by Ukraine, Cuba, Indonesia and Honduras, and furthermore, a record number of more than 40 WTO members joined the dispute as third parties.81

- Constitutional challenge: In March 2012, PMI supported a claim made by British American Tobacco (BAT) in December 2011 before the Australian High Court that plain packaging was in breach of the Australian constitution.82 On 15 August 2012, the Hight Court ruled that plain packaging was not in breach with the Australian constitution as there had been no acquisition of property as alleged by the tobacco companies.81

- Bilateral Investment challenge: In 2011, PMI started legal proceedings against the Australian government for allegedly violating the terms of The Australia – Hong Kong Bilateral Investment Treaty.83 In December 2015, The Permanent Court of Arbitration issued a unanimous decision that it had no jurisdiction to hear the claim. For more information on all three claims go to Australia: Challenging Legislation.

- Executive Decree No. 611 passed on 3 June 2010 in Panamá. Philip Morris Panamá joined onto a claim of unconstitutionality brought by British American Tobacco (BAT) against a ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) and tobacco product display at the point of sale. BAT Panama claimed the ban violated freedom of expression and property rights, among others. The Supreme Court ruled in May 2014 against BAT, noting that, among other things, freedom of expression could be restricted in order to protect public health.84

- 2010 Amendment to the 1973 Act relating to the Prevention of the Harmful Effects of Tobacco (the Tobacco Control Act) in Norway. The Norwegian display ban on tobacco products came into effect on 1 January 2010 after an amendment was passed by the government in favour of the prohibition of visible tobacco products, smoking accessories and vending machines of tobacco products. PMI unsuccessfully challenged the ban as imposing a barrier to trade; the Oslo District court ruled in favour of the display ban in September 2012.85

- Ordinance 514, dated 18 August 2008, and Decree 287/009 dated 15 June 2009 (Uruguay). PMI unsuccessfully challenged the Uruguayan Tobacco Control Act which included a mandate for 80% health warnings on tobacco packets. The case was decided in favour of public health in 2017.86 PMI brought its claim under the Switzerland-Uruguay Bilateral Investment Treaty at the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes. The tribunal ruled in favour of Uruguay in July 2016.87

Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products

As the harms from conventional products have become better understood, and tobacco control measures have been put in place, the cigarette market – from which tobacco companies make most of their profits – has started to shrink. To secure the industry’s longer-term future, transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) have invested in, developed and marketed various newer nicotine and tobacco products.88

In January 2017, PMI issued a press release which stated that the company intended to move its business away from conventional tobacco products entirely (see Image 2).89 The company’s much publicised vision for a “smoke-free” future is one in which PMI plays a central role in “[providing] better alternatives to smoking for those who don’t quit”.3 Integral to this vision was the release of IQOS in 2014. By 2016, PMI was the market leader in heated tobacco products (HTPs), accounting for over 99% of the global HTP market.70 By 2018, PMI’s share of the global HTP market had fallen to around 80%.7090 PMI reported that by the end of 2019, IQOS was available in 52 markets, including the United States (US), and a number of lower income countries.91

- For more information on IQOS and PMI’s newer products see Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International and Heated Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International.

- See also PMI’s Promotion of IQOS Using the FDA’s 2020 Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) Order

In April 2019, a life insurance company Reviti was launched. Registered in the UK at Companies House, Reviti is a wholly owned subsidiary of PMI.9293 The London-based company specialises in offering policies to smokers, with discounts for those who reduce or switch to PMI’s newer products.94

In May 2022, PMI made an offer of US$16 billion deal to acquire Swedish Match, a manufacturer of snus and nicotine pouches, as well as chewing tobacco, snuff and cigars.9596 Swedish Match had planned to sell its cigar business but these plans were put on hold in March 2022.97 PMI CEO Jacek Olczak said of the deal: “An important aspect of this proposed combination is the opportunity in the U.S., which is the world’s largest market for smoke-free products.”98PMI is also hoping to significantly increase its market share of newer nicotine products in Europe and Asia.99

As of 28 November 2022, PMI had acquired over 90% of Swedish Match, gaining control of the company and enabling it to buy the remaining shares and take Swedish Match off the stock market.100101

- For details see Swedish Match

Tobacco companies, including PMI, also invest in therapeutic products, such as nicotine lozenges, gum and inhalers. More information can be found on this page: Tobacco Company Investments in Pharmaceutical & NRT Products

“Smoke-Free” Campaigns

PMI has run various “smoke-free” campaigns promoting its newer products, including “Hold My Light” (UK); “Unsmoke Your World” (global); “It’s Time” (targeting policy makers); and “Futuro sin Humo” (in Mexico).

- For details see: Philip Morris International: “Smoke-Free” campaigns

Participation in Global Platforms to Rehabilitate Image

PMI has attempted to gain access to many high-level international events as a means of “rehabilitating its image and securing influence over global institutions and policy elites”. Since January 2019, PMI presence has been documented at:70

January 2019

- World Economic Forum (WEF; Davos, Switzerland): PMI launched its first “white paper” to coincide with WEF. Though it was not an invited guest, PMI held a side-event co-hosted by the Wall Street Journal, and sponsored the Davos Playbook, Politico’s daily newsletter distributed to attendees.

June 2019

- (Group of 20) G20 Summit (Osaka, Japan): PMI took out a two-page advertisement in The Japan Times promoting its corporate transformation and reiterating the need for dialogue between decision-makers and industry.

- Cannes Lions International Film Festival of Creativity (Cannes, France): PMI attended Cannes to talk about newer tobacco products and potentially recruit celebrity activists to its cause.102 In addition, PMI had its own schedule of events, hosted by actress Rose McGowan and rapper Wycliff Jean. It also spoke in the festival’s Good Track stream alongside organisations including Greenpeace and UN Women. The decision to include PMI on the Good Track was heavily criticised in the light of “the ethics of proclaiming a smoke-free philosophy while continuing to sell billions of cigarettes a year”.103104

October 2019

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA; New York City, USA): Though barred from participating directly in the UNGA, PMI hosted a parallel event at Concordia, a high-level event to foster partnerships between businesses, governments and UN agencies. In attendance were officials from the UN’s World Food Program, the UN Foundation and the World Bank as well as PMI’s Vice President of Global Partnerships and Cooperation, who spoke at the event. Bob Eccles, a paid PMI advisor, spoke at the UNGA during a side event on Exclusion and Engagement in Sustainable Investing.

TobaccoTactics Resources

- PMI Mobilised Support from Retailers

- PMI’s Anti-Plain Packaging Lobbying Campaign

- PMI’s Anti-PP Media Campaign

- PMI’s “Illicit Trade” Anti-Plain Packaging Campaign

- PMI IMPACT

- Philip Morris vs the Government of Uruguay

- Philip Morris’ PR Campaign Against the Display Ban

- Philip Morris’ Regulatory Litigation Action Plan Against the Display Ban

- Philip Morris’ Marlboro Brand Architecture

- Codentify

- Motorsport Sponsorship

- Digital Coding & Tracking Association (DCTA)

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World: How it Frames Itself for a detailed analysis of the ways in which the Foundation portrays itself and those who oppose the Foundation, plus the counter evidence to these portrayals

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World People

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World Grantees

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World Centres of Excellence

- Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International

- Heated Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International

Relevant Links

- Read the STOP report: Addiction At Any Cost: The Truth About Philip Morris International

- Philip Morris International company website

- Cancer Council Australia’s Critiques of KPMG Australia illicit tobacco trade reports

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World website

- PMI Impact website

TCRG Research

- The Philip Morris-funded Foundation for a Smoke-Free World: tax return sheds light on funding activities, T. Legg, S. Peeters, P. Chamberlain, A. Gilmore, The Lancet, 2019, 393(10190):2487-2488

- The revision of the 2014 European tobacco products directive: an analysis of the tobacco industry’s attempts to ‘break the health silo’, S. Peeters, H. Costa, D Stuckler, M. McKee, A. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2016, 25(1):108-117

- ‘It will harm business and increase illicit trade’: an evaluation of the relevance, quality and transparency of evidence submitted by transnational tobacco companies to the UK consultation on standardised packaging 2012, K. Evans-Reeves, J. Hatchard, A. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2015, 24(e2):e168-e177

- Illicit trade, tobacco industry-funded studies and policy influence in the EU and UK, G, Fooks, S. Peeters, K. Evans-Reeves, Tobacco Control, 2014, 23(1):81-83

- Transnational tobacco company interests in smokeless tobacco in Europe: Analysis of internal industry documents and contemporary industry materials, S. Peeters, A. Gilmore, PLoS Medicine, 2013, 10(9):1001506

- Towards a greater understanding of the illicit tobacco trade in Europe: a review of the PMI funded ‘Project Star’ report, A. Gilmore, A. Rowell, S. Gallus, A. Lugo, L. Joossens, M. Sims, 2013, Tobacco Control, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051240

For a comprehensive list of all TCRG publications, including research that evaluates the impact of public health policy, go to the Bath TCRG’s list of publications.

References

Categories

- Advertising Strategy

- Altria

- Arguments and Language

- Brazil

- Challenging Legislation

- Countering Critics

- E-cigarettes

- EU

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World

- Freedom of Information Requests

- Germany

- Harm Reduction

- Heated Tobacco Products

- Hiring Independent Experts

- Illicit Tobacco Trade

- Influencing Science

- Leaked Tobacco Industry Documents

- Legal Strategy

- Lobbying Decision Makers

- Mexico

- Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products

- Philip Morris International

- Plain Packaging

- Snus

- Third Party Techniques

- UK

- Uruguay

- USA